I love mayapples. They look like a prank. Like someone picked a bunch of leaves off of something bigger and stuck them in the ground so they could trick people into thinking that that’s how a mayapple grows. They’re patently ridiculous and fantastic.

I remember the first time I encountered them. Though I don’t remember when, or where, I do remember seeing a bunch of sprouts that looked like folded beach umbrellas for fairies. I wasn’t sure if they were plants or mushrooms at first — before the leaves fully open, they almost look more like fungi than anything planty.

The other day, my handsome assistant and I were on a walk and ran into a whole patch of them. Even better, some of them had flowers, which also look like some kind of prank. The only thing better is when they fruit, which I, personally, find hilarious. Just one leaf with a big old fruit hanging off of it. It looks like a video game monster. Like you’re supposed to get close, then find out the fruit is actually full of teeth and now you’re out of extra lives.

Anyway. Mayapples are interesting for more than their bizarre looks. They can also be a very useful plant.

Mayapple Magical Uses and Folklore

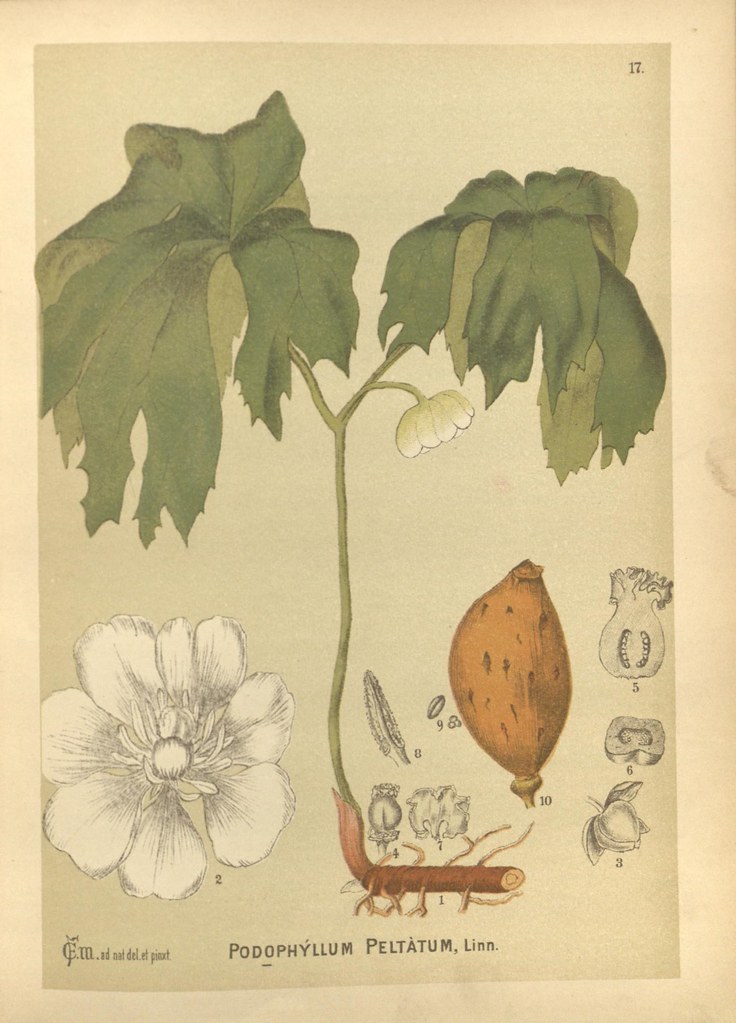

Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum) is sometimes called “American mandrake,” and the name is apt. Like mandrake (Mandragora species), it’s poisonous. It also has a pretty large root that often branches similarly to that of a mandrake.

The name Podophyllum peltatum comes from the Greek words podo, meaning “foot,” and phyllum, meaning “leaf,” as well as peltatum, meaning “shield.” It’s a pretty apt name when you look at their slender stems shielded by broad leaves.

While the entirety of the mayapple is poisonous, the fruit (with the seeds removed) can be eaten only when it is completely ripe1.

Most commonly, mayapple is used as a substitute for mandrake. While the plants are unrelated, their qualities are similar enough to make such a substitution work.

That means that mayapple is an excellent ingredient in protective or banishing formulas. Some people use it as an ingredient in formulas for renewal, rebirth, or new beginnings, largely because of the fact that the plant appears in spring, produces fruit, and go dormant shortly after the fruit ripens in mid-summer.

Interestingly, mayapples have a unique relationship with turtles. While the foliage is bitter and deadly enough for herbivores to avoid it, the smaller guys will happily go after the ripe fruits. Box turtles are actually the primary distributors of mayapple seeds2,3. The fruits grow at just the right height for the turtles to reach them, and the seeds are more likely to germinate after being exposed to the turtle’s acidic digestive environment.

While the mayapple is extremely poisonous, it does have a history of use as a medicinal plant. In the past, it was used as an emetic, anthelminthic, and treatment for skin conditions like warts. Podophyllotoxin, one of its primary toxic constituents, is actually the active ingredient in a topical treatment named Podofilox that’s used to treat some viral skin conditions like genital warts and molluscum contagiosum. It works by inhibiting the replication of cellular and viral DNA as it binds to key enzymes4.

Using Mayapples

If you’re going to use mayapple, do it carefully. Wear gloves. Don’t put it in anything that you’re going to ingest, or even anything that could potentially come in contact with your skin. While the ability to keep DNA from replicating is helpful when you’re trying to kill a skin virus, it’s very much not okay when it’s working on your cells instead.

For real. Be careful.

Whole dried mayapple roots could be used to make an alraun. This is a dried tormentil or false mandrake root (Bryonia alba) used in German folk magic, carved and decorated into a kind of spirit doll. Keeping and properly maintaining one is said to bring good fortune to the household. The alraun (or alraune) would also be bathed in red wine, which could then be sprinkled around the household for protective purposes.

Caring for an alraun is pretty intensive. Once prepared, it needs to be wrapped in a red and white silk cloth, put in a special case, and bathed in red wine every Friday. On each new moon, it should be given a new shirt. These dolls were also passed down through families, though they must be inherited in a particular way: When the father of a family dies, his eldest son may inherit the alraun by placing a piece of bread and a coin in his father’s coffin. If the eldest son dies, his eldest son (or younger brother, if he has no sons) may likewise inherit the alraun by the same method5.

If creating and caring for an alraun seems a bit intense, you can also use dried mayapple in container spells. Just make sure to wear gloves while handling it, and don’t place it anywhere where children or animals may come in contact with it.

Rinse the dried root in water or alcohol and sprinkle it around anywhere you wish to protect. Again, be cautious not to get it on your skin.

The seeds would be useful in formulas for rebirth or renewal. However, as mayapple has never particularly called to me as a “renewal” herb, I can’t offer any more in-depth suggestions here.

Mayapples are beautiful, unusual little plants. They pop up in spring in all of their bizarre glory, flower, fruit, and are gone by late summer. Treated with respect, they can be very useful — even heirloom-worthy — magical tools.

- Mayapple: Pictures, Flowers, Leaves & Identification | Podophyllum peltatum. https://www.ediblewildfood.com/mayapple.aspx.

- Braun, J., & Brooks, G. R. (1987). Box Turtles (Terrapene carolina) as Potential Agents for Seed Dispersal. American Midland Naturalist, 117(2), 312. doi:10.2307/2425973.

- Rust RW, Roth RR. Seed Production and Seedling Establishment in the Mayapple, Podophyllum peltatum L. The American Midland Naturalist. 1981;105(1):51. doi:10.2307/2425009

- Podofilox (topical) monograph for professionals. Drugs.com. (n.d.). https://www.drugs.com/monograph/podofilox-topical.html

- Deutsche Sagen, herausg. von den Brüdern Grimm. Google Books. https://books.google.com/books?id=SRcFAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA135. (In German.)