So, something funny happened.

Two years ago, I purchased a set of three elderberry starts. (Not quite saplings, since they were still very tiny.) I planted them, looked after them, and then pretty much let them do their thing once they got established. When I noticed buds on one, I was very excited — it was a little early for a baby elderberry to put out flowers, but so what? Elderberry flowers!

Except…

Don’t get me wrong. They’re beautiful and vibrant. They’re just also extremely not elderberries.

Couldn’t be farther from elderberries, actually. This small tree is a stunning example of a Lagerstroemia — also known as the crape (or crepe, or crêpe) myrtle.

While I was looking forward to experiencing my first home-grown elderberries this year, I am willing to settle for a very pretty crape myrtle. This tree isn’t native to this area (in fact, there are no Lagerstroemia species native to the US), but it’s very common in the southeast and the seeds have become a food source for birds like goldfinches, cardinals, and dark-eyed juncos, among others. While I’m far more in favor of planting native plants, the fact that many native species of birds have shifted to using crape myrtle seeds as a winter food source is a very big (and legitimately fascinating) deal. If left unchecked, crape myrtles can produce a lot of seeds and will multiply prolifically. If native bird species are taking to crape myrtle seeds as a winter food source — and even seemingly preferring them to commercial bird seeds — that’s a good thing. It allows these birds to take the place of their natural predators and may keep volunteer crape myrtles from becoming a problem.

But enough about my myrtle problems. Here’s some more neat stuff about myrtles in general.

Myrtle Magical Uses and Folklore

Crape myrtles (Lagerstroemia) are native to parts of Asia, Australia, and the Indian subcontinent, and they’re somewhat distantly related to what we usually consider myrtles (Myrtus). Same with lemon myrtles (Backhousia citriodora), which are found in Australia.

Myrtus species can be found in the Mediterranean, western Asia, India, and northern Africa. Lagerstroemia, Backhousia, and Myrtus are genera in the order Myrtales.

There are also bog myrtles (Myrica gale), which are found pretty much anywhere in the northern hemisphere where you can find bogs, and bayberries (like Myrica pensylvanica, M. carolinensis, M. californica, and a whole bunch of others). These are wax myrtles, part of the order Fagales, and are actually more closely related to beech trees.

(Vinca, also known as “creeping myrtle” or “lesser periwinkle,” is not related to myrtles. It’s also a bit of an invasive nightmare here.)

For the purpose of this post, I’m going to focus on members of Myrtaceae.

(Wax myrtles, you’ll get your turn. Promise.)

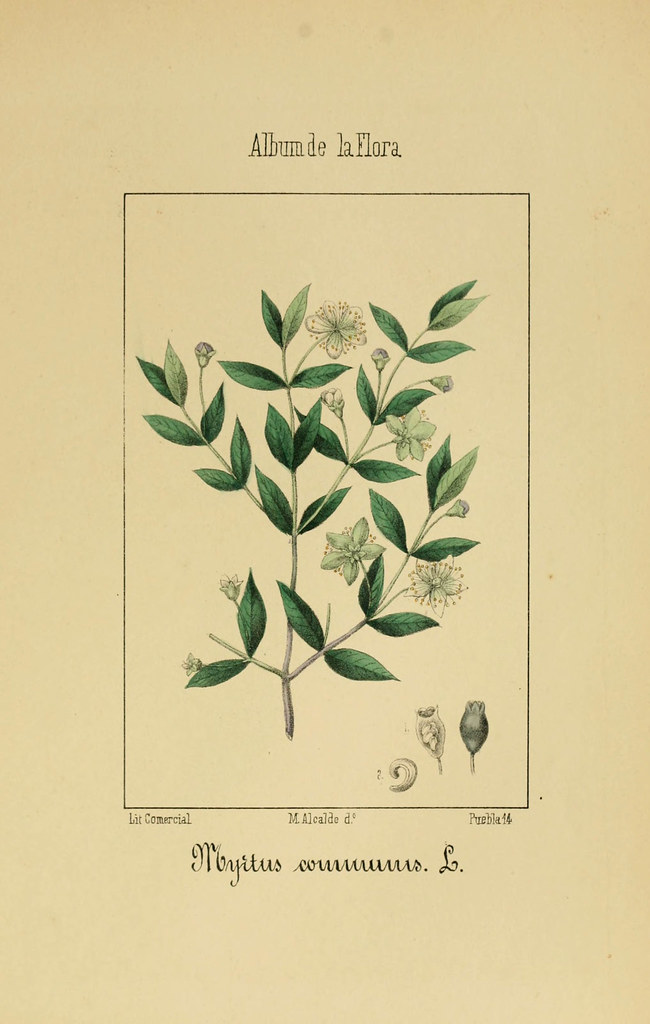

Common myrtle (Myrtus communis) is used as a culinary herb and medicinal plant. Figs, threated onto a myrtle skewer and roasted, acquire a unique flavor from the essential oils present in the wood. The seeds, dried and ground, have an interesting, peppery flavor often used in sausages. As a medicinal plant, it’s been used to treat scalp and skin conditions, to stop bleeding, and to treat sinus problems. (Unfortunately, there’s limited evidence that myrtle really does much for that last one.)

Lemon myrtle (Backhousia citriodora) is also a culinary and medicinal plant. As a culinary herb, it’s used to flavor any dish you might flavor with lemon: desserts, fish, poultry, or pasta. It’s especially useful for flavoring dairy-based dishes, since the acidity of actual lemon juice tends to ruin the texture of milk products.

Medicinally, the oil has some pretty significant antimicrobial activity. The leaves themselves are also very relaxing.

(I’ve had the dried leaves in tea, where I find it really shines — it’s got a delightful citrusy flavor with a bright, subtly sweet taste, and it absolutely knocks me out.)

In ancient Greece, the myrtle tree was a sacred tree for Aphrodite and Demeter. Seeing one in a dream or vision was considered good luck if you were either a farmer or a woman. It was also connected to the minor deity Iacchus, for whom there isn’t really much information — he was often syncretized with Dionysus, and Dionysus was all about wreaths and garlands. He could also have been a son of Dionysus, a son of Demeter, or a son of Persephone.

There are also three ancient Greek origin stories for the common myrtle. In one, an athlete named Myrsine outdid all of her rivals. In retaliation, they killed her and the goddess Athena turned her into a beautiful myrtle tree. In another, a priestess of Aphrodite broke her vows to get married (either willingly or unwillingly, depending on the version). Aphrodite then turned her into a myrtle tree, either as a punishment (for willingly breaking her vows) or as protection (against the husband who abducted her to marry). In the third version, a nymph turned herself into a myrtle tree in order to avoid Apollo’s unwanted advances.

In Japan, crape myrtles are known as sarusuberi (百日紅). Their striking flowers are often found in traditional artwork and make very striking bonsai.

Crape myrtles don’t have much history in old grimoires or European magical systems, purely because they weren’t really around centuries ago. When you’re reading about largely European folk magic, ceremonial magic, mythologies, or herbal medicine, they’re going to be talking about Myrtus species, not Lagerstroemia. That said, crape myrtle flowers are associated with general positivity, love, and romance.

Lemon myrtles don’t have much history in European magical systems, either. Like crape myrtles, this doesn’t mean that they don’t have value. In modern western magic, lemon myrtle is usually considered a solar herb and all of its attributes: purification, positivity, luck, and protection.

As a plant of Aphrodite and Demeter, common myrtle makes a good offering for either of these deities. (This isn’t always the case — sometimes, when a plant is sacred to a god, it means don’t touch that plant.) Since these goddesses are shown wearing wreaths of myrtle, it’s not a terrible idea to weave a myrtle wreath and either wear it while doing devotional work, or place it as an offering to one of them.

Common myrtle is also very strongly associated with love and marriage. In Eastern Europe, myrtle wreaths were held over the heads of a marrying couple (now, people use crowns instead). All the way across the sea, in Appalachia, one method of love divination involves throwing a sprig of myrtle into a fire. If you watch the smoke closely, it’s said to form the shape of your true love’s face.

Myrtle is more than a love and marriage herb, however. It’s also considered protective. As mentioned in myrtle’s Greek origin stories, two of them describe women turning (or being turned) into myrtle trees in order to escape men. In England, it was also thought that blackbirds used myrtle trees to protect themselves against malevolent sorcery.

Common myrtle is associated with Venus and the Moon. Lemon myrtle is associated with the Sun.

Using Myrtle

If you have access to dried common or lemon myrtle as a culinary spice, you’re in luck — these are ideal ingredients for kitchen witchery. Combine them with other ingredients that match your intention (for example, make a delectable chamomile and lemon myrtle tea for luck, just be ready for a nap first), ask the herbs for their help, and you’re good to go.

Lemon and common myrtles have a high concentration of essential oils, so they’re good for infusing. Place some of the dried leaves in a carrier oil, like sweet almond or jojoba, and allow them to sit in a warm, dark area. Shake them regularly, and decant or strain the oil after a month or so. You’ve made an oil you can use for anointing, dressing candles, you name it.

If you want to use common myrtle for love divination, brew a cup of myrtle tea and read the leaves. You can also toss a branch of fresh myrtle into a fire and read the smoke.

I wouldn’t recommend planting myrtle trees if you live outside of their native range, but, if you’re in the southeastern US like me, you probably have access to loads of them anyway. You can find lemon myrtle in tea and spice shops. Same with common myrtle. Crape myrtle grows by the roadsides here as a landscaping plant. (If you’re me, you might even think you’re planting an elderberry start and end up with a crape myrtle instead!)

Even if you can’t grow myrtles yourself, I recommend experiencing their delightful colors, flavors, and aromas at least once. Each myrtle species and relative has their own fascinating folklore and history of use,