You walk into a crystal shop.

To the SOUTH, there is a DOOR.

To the NORTH, there is a glass SHELF.

>go north

You approach the SHELF. There is a variety of yellow and orange CRYSTALS on it.

>seduce shelf

...

>attack shelf with sword

We're going to be here for a while.

>identify crystals

Finally. There is a CITRINE, a TANGERINE QUARTZ, a LEMON QUARTZ, an OURO VERDE QUARTZ, and a GOLDEN HEALER.

>pick up lemon quartz

Okay, but that one's not the lemon quartz.

>pick up golden healer???

Also wrong.

>wtf

Beats me, buddy. I didn't name them.

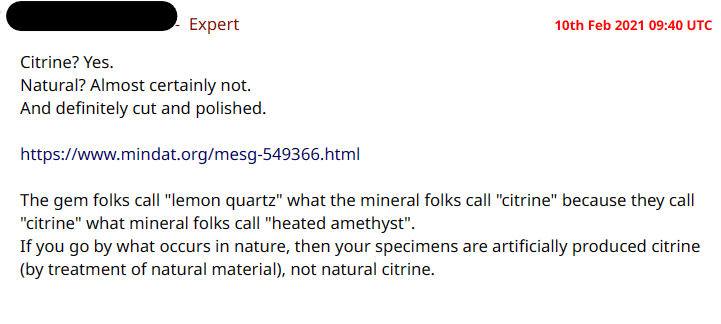

Before I get into this, there’s a quote on a Mindat thread that I think sums it up pretty well:

The discussion was on lemon quartz versus citrine, with one poster attempting to discern if their specimens were natural, untreated citrine. If it seems kind of confusing… it probably should, to be honest.

I’ve written about citrine in the past, and I think I did an alright job of covering the chemical and physical properties of natural citrine and heat-treated amethyst. This time, I’d like to look at a couple of other semi-related mineral specimens.

What is lemon quartz?

Lemon quartz is a variety of quartz that presents with a light yellow color. It’s unmistakably yellow, too — not the toasty orange of heated amethyst, or the smoky yellow, apple juice hue of a lot of natural citrine.

So, is it dyed? Irradiated? Cooked? What’s the difference between one type of yellow quartz, and another type of yellow quartz? While it does certainly seem like some lemon quartz is just light, very yellow citrine, this isn’t always the case.

Ouro Verde quartz, which is also called lemon quartz, is a treated gemstone with a greenish yellow color. These are made by heating irradiated, very dark smoky quartz. (There’s a very interesting explanation of the treatment and discovery of this quartz here.)

To sum up: Specimens sold as lemon quartz may be either particularly yellow citrines, or a bright greenish yellow quartz produced by irradiation and heat treatment.

Is your stone a lemon quartz?

With all of the above in mind, how do you know if you have natural lemon quartz?

As I briefly explained in my post about citrine and heat-treated amethyst, the best way to tell is to observe how the stone behaves in light. Hold it up to a polarized light source and turn it from side to side. Does the color seem to shift a bit from one angle to the other? The stone is exhibiting pleochroism, a hallmark of natural citrine. If the stone is very yellow, that citrine can also be considered a lemon quartz. Heated amethyst doesn’t exhibit this phenomenon, and neither would irradiated and heated clear quartz.

It should also be noted that, in their natural forms, crystals don’t often exhibit the kind of bright hues you can get from heating and irradiating stuff. If it’s really bright yellow — bright, sunny, lemon-candy-highlighters-and-pineapple-Fanta yellow — it’s likely had some help getting there.

Okay, so… What about tangerine quartz?

Look, you pick a fruit, and there’s probably someone online selling quartz named after it. It’s like when people were posting about “strawberry makeup” and “latte makeup,” when what they really meant was “pink blush and eyeshadow” or “different shades of tan eyeshadow and also maybe some bronzer.”

Gem folks and mineral folks very often don’t use the same names for things. In the gem trade, having something that sounds new, unique, and exotic helps you stand out and improves the marketability of your stones. Mineral folks are more concerned with identification, so interesting new names are more of a hindrance than a help. Neither is necessarily better, they’re just two ways of approaching vastly different goals.

The trade names that stones are given don’t need to have any real meaning or relation to the stone’s actual composition. They don’t even have to relate to each other. While they’re both citrus-y, natural lemon quartz is yellow citrine and tangerine quartz is quartz with a coating of iron oxide.

You’ve probably seen or heard of aura quartz before. This is quartz that is colored by vapor deposition, in which the stone is coated with a micro thin layer of vaporized metal ions. This thin layer of metal gives it a shiny, brightly colored finish, and the specific metal ions you use determine the final color.

Sometimes, a process similar to this can occur in nature. Tangerine quartz is quartz that has received a blanket of iron oxide particles at some point during its formation, giving it an orange color. Depending on when this happens, the iron oxide may be present as phantoms or inclusions within the stone. Sometimes, it’s just a surface coating.

When nature throws quartz and various metal oxides together, you can get some really funky-looking crystals. I saw a tiny double-terminated quartz the other day that had so much iron oxide in/on it, it looked like red jasper. Wild.

If tangerine quartz is quartz and iron oxide, then what are golden healers?

Quartz and iron oxide. It’s just that sometimes iron oxide is yellow instead of orange or red.

Golden healers are often the color of citrine, but they get their color by the same mechanism that tangerine quartz does. Quartz grows, a coating of metal particles happens to it, et voilà — you get a golden yellow crystal.

Arkansas, in particular, is home to a beautiful variety of naturally occurring quartz sometimes sold as “solaris quartz.” As these stones form, they receive a layer of iron and titanium. It gives them an interesting golden yellow-orange color (and sometimes a bit of iridescence, too).

Any type of quartz can be a golden healer, as long as the right conditions are met. I have a few Herkimer quartz specimens that are totally or partially covered in golden yellow iron oxide. I’ve even seen amethysts with the typical golden healer coating.

As an aside, golden healers are unrelated to wounded healers, though you can have a crystal that’s both a golden and wounded healer. In metaphysical circles, wounded healers are crystals that have either been damaged at some point or have broken and self-healed during their formation. I’m told that these are considered some of the best crystals for crystal healing, as they have experienced what it’s like to be “injured.”

How do their metaphysical properties differ?

This is a bit of a tricky question to answer. The closest I can come is probably, “what do colors mean in your tradition?”

Lemon quartz can be used the same way as citrine, because it is — it’s just on the yellower end of the spectrum. Ouro Verde quartz, as a treated quartz, is still perfectly fine any situation in which you’d choose a yellow or green stone.

Golden healers and tangerine quartz aren’t super different. Golden healers sometimes include titanium ions, and sometimes are just coated with yellow iron oxide. Tangerine quartz is more orange. Use golden healers in situations that call for the color yellow or gold, and tangerine for those that call for the color orange.

In a lot of guides to color magic, yellow is associated with the element of Air, the intellect, friendship, and joy. Orange is associated with the element of Fire, creativity, willpower, and optimism. Green is connected to the element of Earth, prosperity, and fertility. However, all stones are innately connected to the element of Earth because they’re stones. Where the line falls between “yellow” and “green” or “yellow” and “orange” is also highly subjective.

For this reason, I’m hesitant to point to a specific metaphysical use for these minerals. Use the one that seems to volunteer to you. I guarantee, even if you pick the “wrong” kind, nobody is going to explode. Consider it a helpful exercise for your intuition!

The fact is that nature abhors absolutes. Everything — and I do mean everything — exists on a kind of gradient. At what point does a citrine become a lemon quartz, or a golden healer become a tangerine quartz? The only answer I can really give you is, “when it seems like it.” Trade names shouldn’t influence how much you enjoy your stones (or how you use them). It’s fine to be curious about how things get the names they do, but don’t give your power away to what is, a lot of the time, just a marketing gimmick.