Hello!

My passionflower is loving this weather, though the rest of the plants here seem less than enthused about the whole thing. It’s not only encompassed half the porch, it’s climbed nearly up to the roof and sent out several tendrils along the lawn. If it didn’t also put out beautiful flowers and a ton of fruit, and act as a cozy little haven for sleepy bees, I’d be tempted to cut a bunch of it down.

That got me thinking — if I did, what would I do with that much passionflower? I can only tincture so much of it. Could I weave it into baskets? Turn it into rope?

Vines, in general, have a long history as religious symbols, the subject of legend and folklore, and magical ingredients. If you, too, are experiencing a sudden flush of viny plants that you don’t know what to do with, folklore may have some ideas for you.

Vine Magical Properties and Folklore

In the Ogham writing and divination system, the letter muin (ᚋ) is commonly interpreted as “vine,” and usually portrayed as either grape or ivy. However, grapes are not native to Ireland and, even when they were introduced, they never really took root there (pun intended — Ireland is not a great place to try to grow grape vines). The word “muin” also doesn’t have anything to do with vines. Instead, it refers to a thorny thicket. This has made muin one of the most controversial and seldom-agreed-upon parts of the Ogham.

The ancient Greek deity of wine, orchards, frenzy, fertility, and religious ecstasy, Dionysus, is also intimately connected to vines. (And I do mean intimately.) Not only are grape vines his domain, he is also regularly portrayed as wreathed in ivy vines. Here, the evergreen nature of ivy represents the gods’ immortality. It’s also connected to fertility and sex.

Dionysus isn’t the only one to wear an ivy crown, either. Thalia, Muse of Comedy, is also portrayed as wearing one.

In Egyptian legend, Osiris is associated with the ivy, again, because of the plant’s connection to immortality and rebirth.

There’s a Persian (now modern day Iranian) legend that tells of the origin of wine. Long, long ago, a bird dropped some seeds by a King’s feet. Intrigued, the King had the seeds planted and cared for. The seeds became sprouts, the sprouts became vines, and the vines grew heavy with grapes. Overjoyed, he had the delicious grapes picked and stored in his royal vaults.

However, grapes don’t stay fresh forever. The vault was too damp for them to dry into raisins, and too warm to chill them. Instead, the grapes began producing a dark liquid which everyone assumed was likely a deadly poison. Before the old grapes could be cleaned up and thrown away, one of the King’s wives attempted to end her life by drinking some of the grape “poison.” When the King found her later, she was far from deceased — in fact, she was dancing, singing happily, and apparently thoroughly enjoying being the first person in recorded history to ever get absolutely rocked off her tits on wine. With this evidence that the liquid was not poison and, in fact, seemed to make people quite happy, the King named it “Darou ē Shah” — The King’s Remedy.

No word on what happened to his wife, however. Therapy being in short supply thousands of years ago, one can assume she either eventually found some actual poison or developed an absolutely staggering drinking habit.

Ivy is about more than ecstasy, wine, sex, and living forever, though. One look at the growing behavior of many vines can show you exactly what else they’re good at: binding things. Even the beautiful, gentle passionflower vines climbing my front porch do so due to grasping tendrils of surprising strength and tenacity. Some vines, English ivy in particular, also get a reputation here for damaging property and killing native trees.

Depending on the context, vines are then equally as restrictive as they are freeing. Sometimes, vines are heavy with grapes and the promise of wine, intoxication, inspiration, sexual desire, and ecstasy. Sometimes, they’re ivy vines, evergreen and symbolizing enduring life and lush greenery during the winter months. Other times, they are the vines that grow around things, binding and restricting them like ropes.

Ivy is also associated with protection and healing. This may be due to its connections to immortality and rebirth. Grapes, on the other hand, are associated with fertility, money, and all things connected to the concept of abundance. Briony, on the other hand, is both money and protection. Placing money near a briony vine is said to cause it to increase.

In the tale of Sleeping Beauty, vines (sometimes) play a key role. In the Disney version, Aurora is cursed, pricks her finger, falls asleep, yadda yadda yadda, vines grow and cover everything. In an older telling, it was a dense hedge of climbing roses. One yet older version of the story (Sole, Luna, e Talia) also has Sleeping Beauty-

You know, I’ll just let Giambattista Basile tell it.

“crying aloud, he beheld her charms and felt his blood course hotly through his veins. He lifted her in his arms, and carried her to a bed, where he gathered the first fruits of love.”

Yeah. When that fails to wake her, he pulls his pants up and rides off to his castle and his already existing wife, the Queen. Sleeping Beauty only awakens again when one of the twins she subsequently births tries to nurse and accidentally sucks the splinter from her finger.

(As if that weren’t enough, the Queen gets fed up with the King’s infidelity and tries to have the children cooked and fed to her husband.)

Interestingly, vines aren’t prominent in the assault version of Sleeping Beauty — they become more important the further you get from that version, and the closer you get to Disney’s much more sanitized telling. It’s as if the presence of the vines in the story both bind Sleeping Beauty in her castle and protect her from the King.

No vines? Not even a climbing rose? You’re in for a bad time.

Using Vines

Vines make beautiful decorations for the home and altar. Evergreen ivy is commonly brought indoors during the winter months as a decoration, tied with swathes of ribbon, hung with bells or other ornaments, you name it.

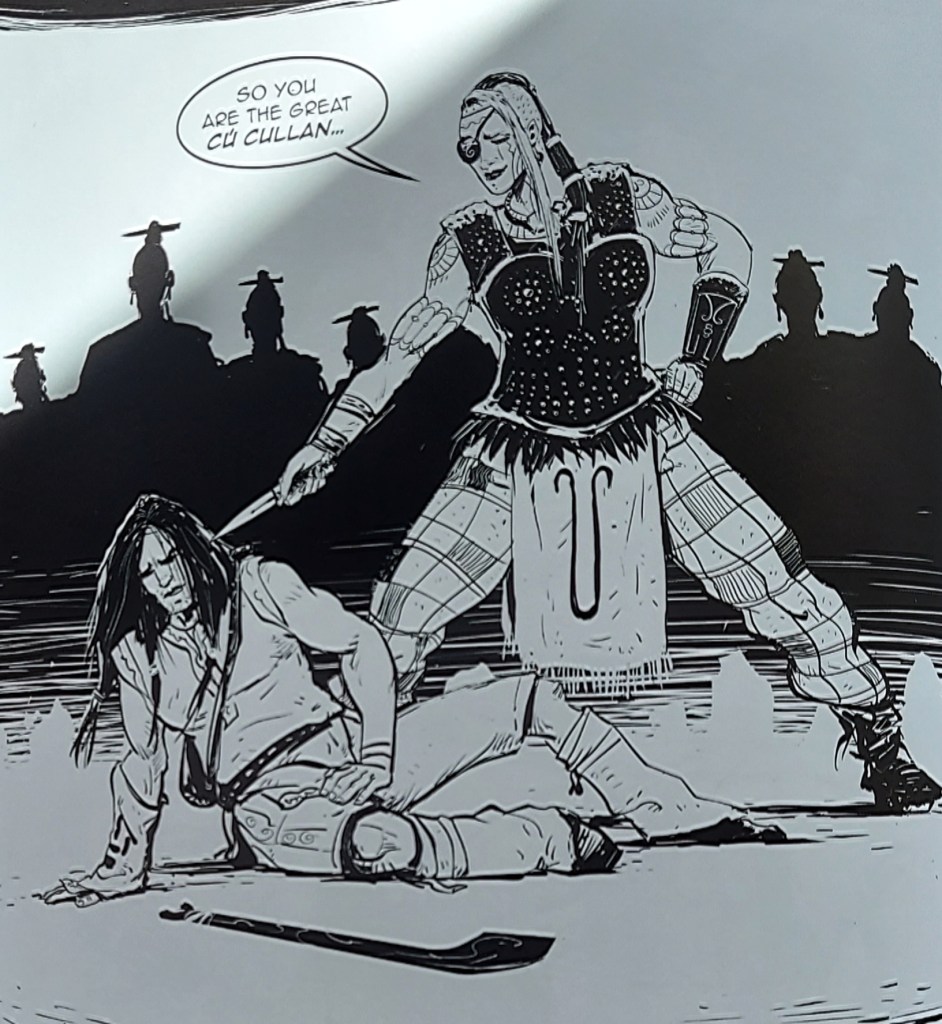

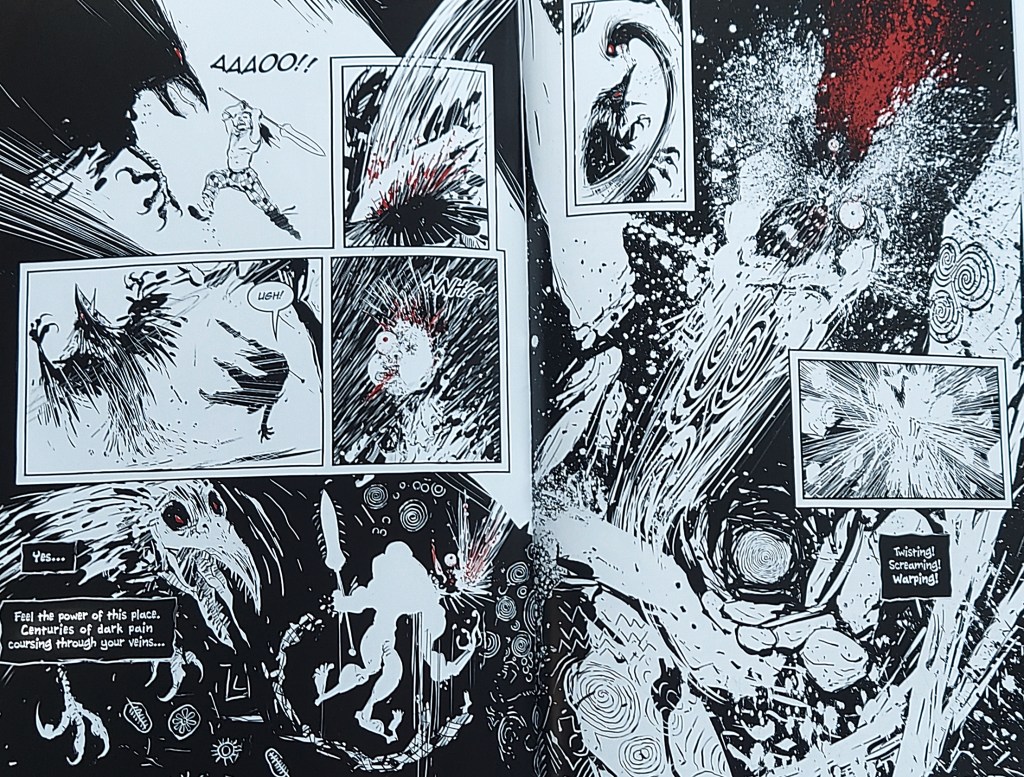

Vines can also be used to bind things. Hollywood has portrayed magical bindings in some… interesting ways. For example, “binding” a witch à la The Craft.

This, however, is silly.

Bindings can go one of two ways: a person, thing, or situation may be bound (in the sense of binding someone with rope) to keep them/it from causing harm or otherwise interfering with you. You can also bind something to yourself. For example, a really great job that you just got, happen to enjoy, and want to make sure that you keep.

In this case, the binding is a form of sympathetic magic. You take a representation of the thing you wish to bind, and effectively tie it up with what you have on hand. (This may be vines, if you want to enlist the vine’s help and magical associations, but can also just be household twine in a pinch.) There are plenty of chants and incantations you can recite while doing so, but I find that it’s most effective if you speak from the heart — inform the subject why they are being bound, and what you hope will come of it. Put it in a jar or box, close it tightly, and keep it somewhere safe so you can undo the binding when the time comes.

To bind something to yourself, you’d use a representation of yourself (like a photo or lock of hair) and a representation of what you wish to bind to you. Wrap both objects together with the vines or string, again speaking from the heart while you do so. Place the objects in a jar or box and keep them somewhere safe.

Bindings aren’t the only type of sympathetic magic that vines are good at, though. Plant a vine (preferably not an invasive species — there are loads of native vines) along with a representation of something you wish to grow. Ask for the vine’s help, and declare that, as the vine grows, so shall grow the thing you desire. Take good care of that vine, and keep an eye on its growth.

While every species of plant has its own magical uses and depictions in legend and folklore, vines are in a class of their own. Each one has their own unique properties, but vining plants also have plenty of common ground.