Vervain (Verbena officinalis) is a prominent herb in European folk and ceremonial magic. Its roots also extend to American Hoodoo.

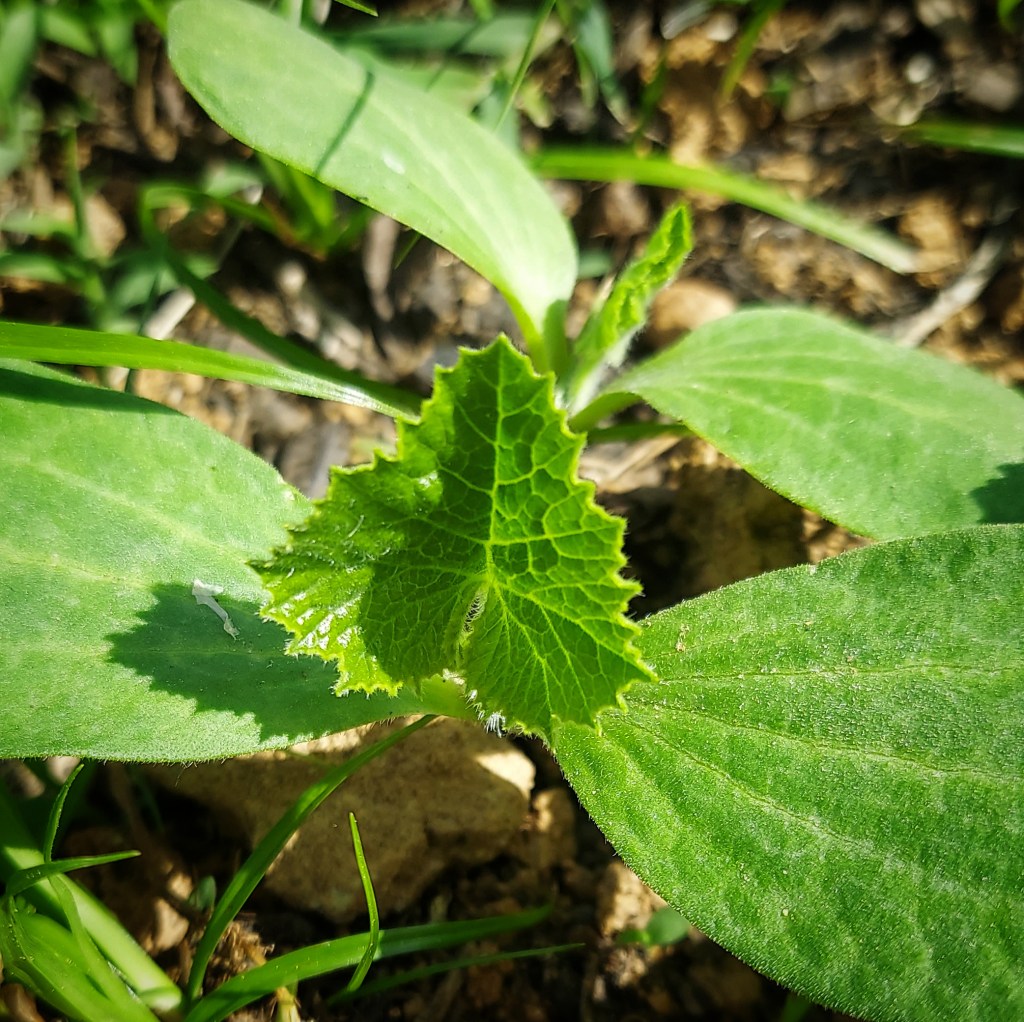

Though most old grimoires mean V. officinalis when they refer to vervain, there are actually about 80 species in the genus Verbena. In my area (and all of the continental US, and fair bit of Canada) we have Verbena hastata, also known as blue vervain. While it’s not the same plant, you’ll often find V. hastata labeled simply as “vervain” in metaphysical contexts.

Lemon verbena, Aloysia citrodora, is also a member of the Verbenaceae family. However, since it’s a somewhat more distant relative, I wanted to limit this post to V. officinalis and V. hastata.

Vervain Magical Properties and Folklore

Vervain is sometimes called “the enchanter’s plant,” since it’s one of the most versatile herbs in European magic. Even outside of Europe, it was (and continues to be) considered a plant of considerable medicinal and spiritual significance.

As John Gerard wrote in 1597,

Many odd old wives’ tales are written of Vervain tending to witchcraft and sorcery, which you may read elsewhere, for I am not willing to trouble your ears with supporting such trifles as honest ears abhor to hear.

Magically, it’s used for purification, protection, divination, peace, luck, love, and wealth. It’s a pretty solid all-purpose herb that is often added to formulas to increase their power.

The name vervain comes from the Latin “verbena,” which refers to leaves or twigs of plants used in religious ceremonies. This, in turn, came from the Proto-Indo-European root “werbh,” meaning to turn or bend.

I have also seen the origins of the word vervain given as a Celtic word “ferfaen,” meaning to drive stones away. However, I haven’t found strong evidence for this origin — all attempts to look up “ferfaen” only yield articles claiming it as the word origin of “vervain,” and most of them only give “Celtic” as the language of origin. One source did cite the Cymric words “ferri” and “maen” as a possible origin, with the word “maen” mutating over time into “faen” to eventually yield “ferfaen.” (Upon further searching, I was not able to find the word “ferri,” though I did find “fferi,” meaning “ferry.” This would give the word “ferfaen” a meaning closer to “ferry away stone(s).”)

Nonetheless, the etymological sources I looked at gave “verbena” as the origin of vervain, not “ferfaen.”

Pliny the Elder credited vervain with quite a lot of magical properties. According to him, it was used to cleanse and purify homes and altars. He claimed the Gaulish people used it in a form of divination, and that Magi said that people rubbed with vervain would have their wishes granted, fevers cooled, friends won, and diseases cured.

Interestingly, he also pointed out that vervain was considered a bit of a party plant, for when dining-couches were sprinkled with water infused with vervain “the entertainment becomes merrier.”

While vervain is strongly associated with the Druids, they didn’t leave a whole lot of records of their activities behind. What we do know is largely through sources like Pliny, and it’s likely because of writers like him that vervain became strongly connected to the ancient Druids.

For the best potency, vervain should be gathered in a specific fashion. It’s best cut between the hours of sunset and sunrise, during the dark moon. Like many other herbs harvested for their leaves, it’s best to cut the leaves before the flowers open. After cutting, it’s best to offer some fresh milk or honey to the plant.

Vervain is thought to be the origin of the name “Van van oil.” While the van van oil recipes I’ve seen don’t include vervain or vervain oil, it’s possible that the Verbena family loaned its name, nonetheless. (In that case, it was most likely lemon verbena, vervain’s citrus-scented South American cousin.)

Vervain is also one of those contradictory herbs that is simultaneously said to be used by witches, but also effective against witchcraft.

In the very distant past, bards would use brews of vervain to enhance their creativity and draw inspiration.

Medicinally, vervain is an emetic, diuretic, astringent, alterative, diaphoretic, nervine, and antispasmodic. According to Hildegard of Bingen, a poultice of vervain tea was good for drawing out “putridness” from flesh.

Using Vervain

Soak some vervain in water, then use the stems to asperge an area, person, or object that you wish to cleanse. It’s also an excellent addition to ritual baths for this purpose.

Sprigs of vervain are also worn as protective amulets, specifically against malevolent magic. Tie a bit with some string, put it in a sachet, and carry it with you. Tuck a sprig of it in the band of a hat. Use a small bud vase necklace and wear a bit of vervain like jewelry.

Planting vervain around your property is said to ward off evil and guard against damage from bad weather. If you choose to do this, please select a variety of vervain native to your area — in most of the US, V. hastata is a safe bet.

V. officinalis is often used medicinally, V. hastata is considered both medicinal and edible, but avoid consuming it if you’re pregnant, trying to become pregnant, or are breastfeeding. Talk to a qualified herbalist if you have any chronic conditions, or routinely take any medications. Avoid consuming a lot of it, since it is an emetic. It’s also important to be sure that the herb you’re working with is really V. hastata or V. officinalis — there are plenty of Verbena species that don’t offer the same benefits.

Vervain is a powerful plant, as long as you know which member of Verbenaceae you’re looking at. If you have the ability to grow a native vervain, by all means do so — these plants are tall, with interesting-looking flower spikes. They’re also easy to dry and store, ensuring that you’ll always have a stockpile of this powerfully magical plant.