Note: This post contains affiliate links to the book(s) I mention. These allow me to earn a small finder’s fee from Wordery.com, at no cost to you. Thank you for helping to support writers, publishers, and this site!

I don’t know if I can express how much I wanted this book using actual, intelligible language words, as opposed to some kind of excited dolphin noise.

I don’t know if I can express how much I wanted this book using actual, intelligible language words, as opposed to some kind of excited dolphin noise.

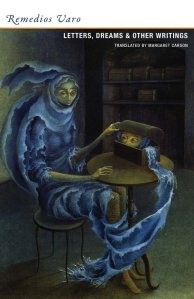

Saying “I love Remedios Varo” would be a little… not actually disingenuous, but small. I find her work inspiring. I love plumbing the depth of detail in her paintings. I’m fascinated by her life. If we had lived around the same time, in the same place, and there wasn’t a language barrier, I like to think we would have been friends (assuming she could get past my overly-eager fanning, but whatever). We could’ve had sleepovers, written letters to people we picked out of the phone book, and rearranged crocodile skulls, pipes, and armchairs together.

Incidentally, she was absolutely weird and I could not be more here for it.

See, what excited me about this book is that my Spanish is execrable, and her letters, notes, and other private writings aren’t widely translated. And by “not widely,” I mean that I’m pretty sure this is the only time they have been.

Letters, Dreams & Other Writings is short, but understandably so — it’s not as if she set out to have her notes compiled into a full-length book. It’s also extremely intimate, including details from several of her dreams. The first section comprises her letters to others (Gerald Gardner, who popularized Wicca, among them). Some of the recipients were complete strangers, and the letters were signed with fake names.

Anyway, this is pretty much all just preamble to my favorite bit: “The Observers of the Interdependence of Household Objects and of Their Influence Over Everyday Life.” I’ll let her describe it:

“This group, active for quite a long time now, has already made important verifications that make life easier from a practical point of view. For instance: I move a can of green paint some five centimeters to the right, I stick in a thumbtack next to a comb and, if Mr. A… (an adept who works in tandem with me) at that same moment places his book on beekeeping next to the pattern for cutting out a vest, I’m sure there will come about, on Avenida Madero, the encounter with a woman who interests me and whose origin I’ve been unable to determine[.]”

There are more descriptions of the private “solar systems” of the members of this esteemed (and, as far as I’ve been able to determine, imaginary) group. Armchairs, velvet shoes, skulls, a pipe inlaid with fake diamonds… All of them are described as laid out in a ritualistic arrangement, though it’s never explained exactly why each particular object has significance.

The Surrealist movement has some very strong ties to witchcraft and the occult (a topic I’d like to get into more deeply with a book focused on the subject). So, it’s unsurprising that Varo had her witchy tendencies, as well. The aspect of the practices of T.O.o.t.I.o.H.O.a.o.T.I.O.E.L. that surprised and intrigued me the most was their interdependence. Varo explains that new members of the group are limited in the objects they may use, and the manner in which they may move them. She goes on to describe committing an infraction:

“I permitted myself to add […] a dried hummingbird stuffed with magnetic dust, all of it well tied with cord, just as mummies are wrapped, using red silk thread. I did so without warning my colleagues, a very serious transgression according to the regulations of the group. Only our leader, with his long experience and his high degree of knowledge, can do something like that without bringing on grave consequences. What’s more, I intentionally put the can of green paint under a beam of red light that was coming through the stained glass pane of my window[.]”

She blames this course of action for a change in her paintings (the sudden, irrepressible desire to paint otherwise placid sheep with staircases coming out of their backs, for one), the ruining of a shirt, and the sudden appearance of a large deposit of salt in her bedroom.

Despite existing in discrete systems of their own, under the care of each member, the objects are all interrelated. Moving one affects things in the homes of other members, and doing so without warning is a serious thing. It put me in mind of crystal grids, and the way they (like all magic) can be used to influence something very far away — you don’t need the patient in front of you to work a healing spell, for example. Only, in Varo’s case, the movement and placement of ritual objects in other homes influences the ritual objects in hers, which, in turn, influences her everyday life.

Only two of her letters discuss this practice at all, which is a shame, because I find it fascinating. Even if she made it up entirely, even if there never was a group of Observers, the description of these magical tableaux conjure up a captivating mental image. The rest of the book is a collection of dreams, a pretend archaeological resource on Homo rodans, a few recipes for inducing specific types of dreams (erotic dreams require, among other things, “1 kilo horseradish, 4 kilos honey, and hats to taste”), and notes on her paintings. It’s a short read, like I said, but was a wonderful way to spend an afternoon that’s left my imagination invigorated.

Great post 😁

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike